“For My Little Baby’s Sake”, by Maude Crawford

As a little treat, we’ve decided to do something we don’t usually do: share a Christmas story from our Archives!

“For My Little Baby’s Sake” was first published in “The People’s Friend” in December, 1913.

It demonstrates the strong moral at the centre of our magazine at the time. So although it’s not exactly cheery, it makes for an entertaining read.

We hope you enjoy!

“Hush, my baby! Hush! No one will refuse us shelter tonight – for it is Christmas Eve! The night that brought a dear little baby to the world – a baby whose coming taught people to be pitiful to little babies, and to the women who bore them!

“For unto you is born this day, in the city of David, a Saviour – and thou shalt call his name Emanuel!”

The woman repeated the beautiful old words as she gathered her shawl more closely round her year-old child, and struggled on – the snow blinding her, the cold wind chilling her through and making her arms quite numb.

The words comforted her, bringing back girlhood’s days not long past in time, but divided from now by suffering which cannot be judged by the ordinary minutes, hours and days. It was past now, and she was travelling as far as she could from the scene of it – to start afresh.

At last the woman’s weary feet had reached the village street

The journey had proved longer than she had expected; for no one seemed to want a woman with a baby. They had slept where they could – under sheltering hedges, in friendly barns.

But tonight – tonight was Christmas Eve, when the world’s heart was warm and open. And such a Christmas Eve, with the snow making itself into wreaths in the lanes, and against every dyke.

At last the woman’s weary feet had reached the village street. The very first house she came to, there was a sound of children’s joyous voices singing a carol:

“Peace on earth, goodwill toward men

From Heaven’s all gracious King!

The earth in solemn stillness lay,

To hear the angel’s sing!”

The woman listened, leaning against the gate of the little villa garden. Tears rose in her tired eyes. Once she had been a little girl at home. She, too, had sung that sweet old carol, and had felt her heart grow soft and glad on this night of the year.

As she went slowly up the path she could see the happy group about the piano through the laths of the venetian blind.

She rang the bell, and heard the message go thrilling through the house, And presently a woman in a great overall came bustling from the kitchen – flour on her hands and wrists.

“Peace on earth, goodwill toward men!”

“Good gracious! Only a horrid tramp! Really the impertinence of the creatures! And me in the midst of making the pastry for tomorrow!”

And oppressed with her Martha-like cares, she turned the key in the door without giving the woman time to say a word, and returned to her work in the cheerful kitchen.

As the woman went slowly down the path again, the clear voices of the children followed her:

“Peace on earth, goodwill toward men!”

She would not be down-hearted. There were plenty of other houses; and the cold would be too much for her little girl tonight.

She walked a little, looking wistfully at the houses, which seemed full of light tonight. And at last she summoned the courage to enter another gateway, and headed to the back this time.

She tapped timidly, and leaned against the stonework, trembling, while she waited.

She rapped again, and then – made bold by despair, and by the child’s restless whimpering – she turned the handle and ventured inside the back door.

“Oh, Sarah! Put him out! Put him out!”

At that moment a great woman servant came bustling from the kitchen on her way to the larder, and gave a loud shriek.

“Mam! Mam!” she shouted. “If there ain’t one of those tramp bodies right inside the house – and in another moment dear only knows if we mightn’t have been killed, and it Christmas Eve and all!”

“Oh, Sarah! Put him out! Put him out! He must have known your master is from home!”

A little, trembling woman appeared in the kitchen door.

“It’s a woman, ma’am,” the servant answered grimly. “They’re the worst. The man will be somewhere outside, you be sure. Out you go! Quick about it! And tell your gang that there’s a bulldog that’s let loose at nights! And if it wasn’t Christmas Eve I’d hand you over to the police!”

“Oh! For my little baby’s sake,” the woman began tremulously. “For Christ’s sake-”

“She’s swearing, ma’am!” the maid said, in genuine horror. “Out you go! And be ashamed of yourself!”

So the woman found herself in the night again.

Strength and spirit were beginning to fail her.

She seated herself on the step of a gate, and looked about her dreamily. There were no stars tonight; the air seemed black with snow.

It was as though a black pall hung between God and the world. Could God see her – pity her – sitting there with her babe?

“I will try again!” she whispered to herself.

She rose wearily, the very thought of her babe rousing her. For herself she would have been glad to let the snow cover her.

“I will try again!” she whispered to herself.

There was no show of Christmas in the house at whose door she rapped. No sound of merriment. And in at the unscreened window she had seen the walls bare of holly or ivy. The door was opened by a tall, stiff-looking lady, in severe black dress.

“Come into the hall!” she said. And gratefully the woman went and sank upon a chair there. It was not a warm or cheerful hall, but it was better than outside.

The lady asked many and searching questions about her past – to some of which the woman seemed loth to reply – then recommended her to the workhouse in the town two miles ahead.

The woman looked at her piteously, and pled for shelter for that one night – for the sake of her babe. But immediately the lady was in haste to get rid of her. And when the woman stood in the path once more with her babe, she heard the old servant, who was locking the door, chiding her mistress.

“I’ve told you, ma’am, that your goodness to tramp bodies would get us murdered in our beds one of these days!”

Down the path the woman went. She could scarcely walk. Bursts of merriment greeted her ears from different houses as she passed. But she approached no more doors.

And then slightly apart from the village – with snow-covered ivy clinging lovingly about it – she came upon the church, and a great longing seized her.

The gentle, pitiful gaze seemed bent upon her.

If that door was open, surely she and her little child would be received there.

She tried the door. It yielded, and she passed inside.

Warmth met her there. The church had been heated for the decorators, whose work was done now.

Slowly she went up the aisle, as though drawn to where the light swung at the alter. Bright holly berries gleamed on every side – the altar itself was a bank of snowy chrysanthemums.

But the woman’s eyes were fixed on a picture of the Christ.

The gentle, pitiful gaze seemed bent upon her.

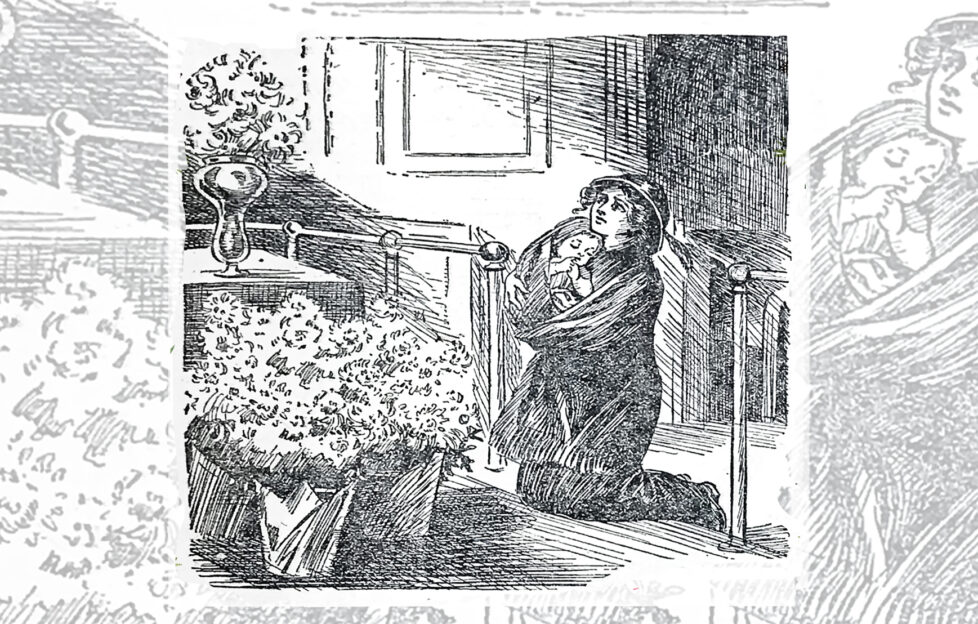

“You will not turn us out!” she whispered, as she sank down on the softly carpeted step.

Next morning the tall, grave-faced clergyman came early through the snow to his little church. He liked to be there before the very earliest of his flock.

“But you have come home, Mary – home at last!” he said almost solemnly.

With his own key he unlocked the door and passed within. And right below the Christ he found the woman lying – the babe still clasped to her breast.

Stooping close he saw that it was a face that used to be the most beautiful of any in his eyes – for whose sake he had remained single.

“Mary!” he murmured – as in his strong arms he lifted both her and her babe, and carried them to the rectory.

An hour later the woman sat in his great armchair before the sturdy fire, and told him her pitiful tale. And the clergyman’s fine face grew troubled as he listened. Then he stooped and kissed her tenderly.

“But you have come home, Mary – home at last!” he said almost solemnly.

When the clergyman got up that day to give his little Christmas address, the people somehow held their breath.

It was usually just one or two cheery words, that suited well with the holly-decked church; today they felt that it was to be different. There was a deep gravity in the eyes that scanned them.

He waved his hand to the pictured Christ, and tears rose in his eyes.

“My people!” he said, and there was a strange solemnity in his deep voice. “I believe that last night the Christ child came knocking at certain of your doors – begging humbly for shelter – and you refused.

“A woman and a child – just as that other woman and child might have done – and you would not. You know the words:

“‘Inasmuch as you did it not to the least of these little ones you did it not unto me!’

“You turned the Christ child from your doors last night!”

One or two in the congregation moved uncomfortably.

“The woman found refuge with her babe here. The Christ did not refuse her – she lay there, at His feet!”

He waved his hand to the pictured Christ, and tears rose in his eyes.

“The woman is called Mary,” he added gravely and simply. “And God has brought her to this place. She is the woman I love – the woman who is to be my wife.”

Into the vestry after, three women came.

“We did not know!” they pled almost tearfully.

“I was so busy and flustered – I really scarcely saw her!” the one who had been making pastry murmured.

“Oh! Martha! Martha!” the minister said reproachfully.

“We will remember the Christ-child another time,” the timid woman said gravely. “We-we just did not think.”

For more fiction content from “The People’s Friend”, click here.

Did you know that subscribers receive their issues of “The People’s Friend” early? Click here for more info.

You can also choose a digital subscription, and read the “Friend” on your tablet, smartphone or computer.