Photographing Tutankhamun

A new exhibition of Harry Burton’s photographs reveals the bigger picture behind the images

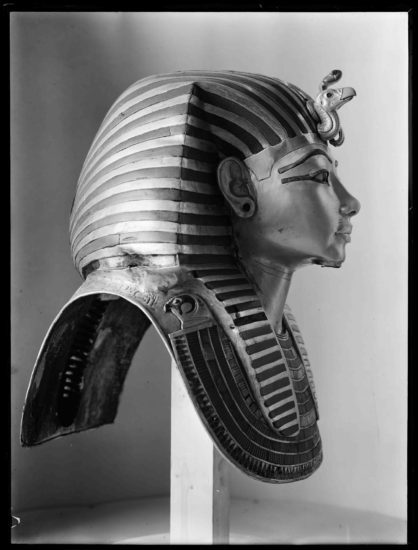

The funeral mask of the Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun is surely one of the most instantly recognisable images of modern times.

But have you ever taken a moment to wonder who took the photograph?

A new exhibition at the University of Cambridge’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology highlights the work of photographer to the pharaoh, Lincolnshire photographer Harry Burton, whose iconic photography documented the decade-long excavation of King Tutankhamun’s tomb.

From Lincolnshire to Egypt

Who was Harry Burton? Born in Stamford, Lincolnshire, in 1879, Harry was the son of a cabinet maker and fifth of eleven children. Harry worked for a time in domestic service for Robert Cust, a man living locally and a scholar of Renaissance art.

When Cust moved to Florence, Harry accompanied him as his secretary. It was in Florence that Harry’s skill for photography blossomed; while there, he met Theodore M. Davis, an American involved in excavating in the Valley of the Kings, who would go on to hire Burton as his photographer.

Harry then became photographer for the Metropolitan Museum’s Egyptian Expedition; when Howard Carter discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, he asked the Met for permission to borrow Harry as his photographer, and he divided his time between both expeditions for the next eight years.

Tutankhamun and the Valley of the Kings

Backed by Lord Carnarvon, archaeologist and Egyptologist Howard Carter had searched the Valley of the Kings for five years, aware that one royal tomb remained unaccounted for. Finally, in 1922, he discovered it essentially intact.

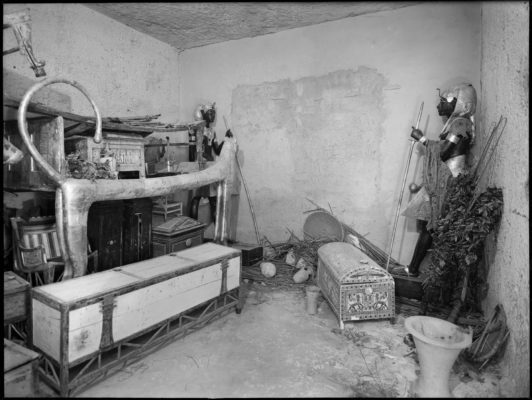

Despite Tutankhamun being a relatively low-key royal, and although the tomb had been robbed shortly after the burial, Carter’s discovery remains the richest such discovery ever made. Harry Burton was there to preserve the unfolding of each step, inspiring a fascination with Ancient Egypt that reached fever pitch in the late 1920s and which continues to this day.

Why Harry’s photography is still important

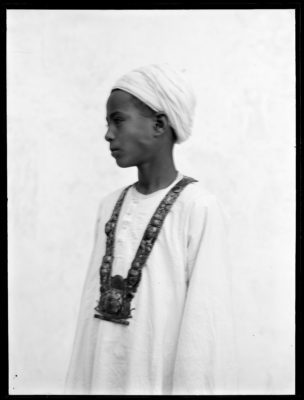

The images Harry captured not only provide a complete photographic record of the excavations and the treasures of the tombs, they help inform our perception of Egypt, ancient and modern, and highlight the contribution made by the hundreds of Egyptians who worked alongside the British and Americans.

Men, boys and girls were hired to excavate earth from the discovery site – arduous work, in temperatures often close to 100 degrees. Artefacts from the tomb would then be placed in crates, which were pushed along a lightweight rail track, ready to be loaded onto a barge for the two-day journey to Cairo.

Shaping the way we think about the past

In all, Harry took around 3,400 photos of the excavations, and first to study the collection in its entirety is Curator of the exhibition, Dr Christina Riggs.

Talking to the ‘Friend’, Dr Riggs explains, “Tutankhamun usually makes us think of gold, but going back to these photographs is a chance to take a fresh look, in black and white – and to see how much work, including the work of many Egyptians, went into the discovery. Photographs shape the way we think about the past, so understanding why and how different images were taken is important. I notice something new almost every time I look at one of Harry Burton’s pictures, and I hope people who visit the exhibition will enjoy having the same experience.”

What you’ll see at the exhibition

Using digital scans from the original glass-plate negatives, more than two dozen images have been specially created, some of which have never been seen before. This image of a local boy wearing one of the discovered necklaces had, until now, never been printed from the negative.

Also on display are newspaper and publicity materials from the 20s and beyond, showing how the photographs were used in print. The digital scans were made at the Griffith Institute at the University of Oxford, home to excavator Howard Carter’s own records.

Photographing Tutankhamun is being held at Cambridge University’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA) until 23 September. Staged with support from the British Academy, UEA, and the Griffith Institute at Oxford University, entry is free.

All images courtesy of the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford