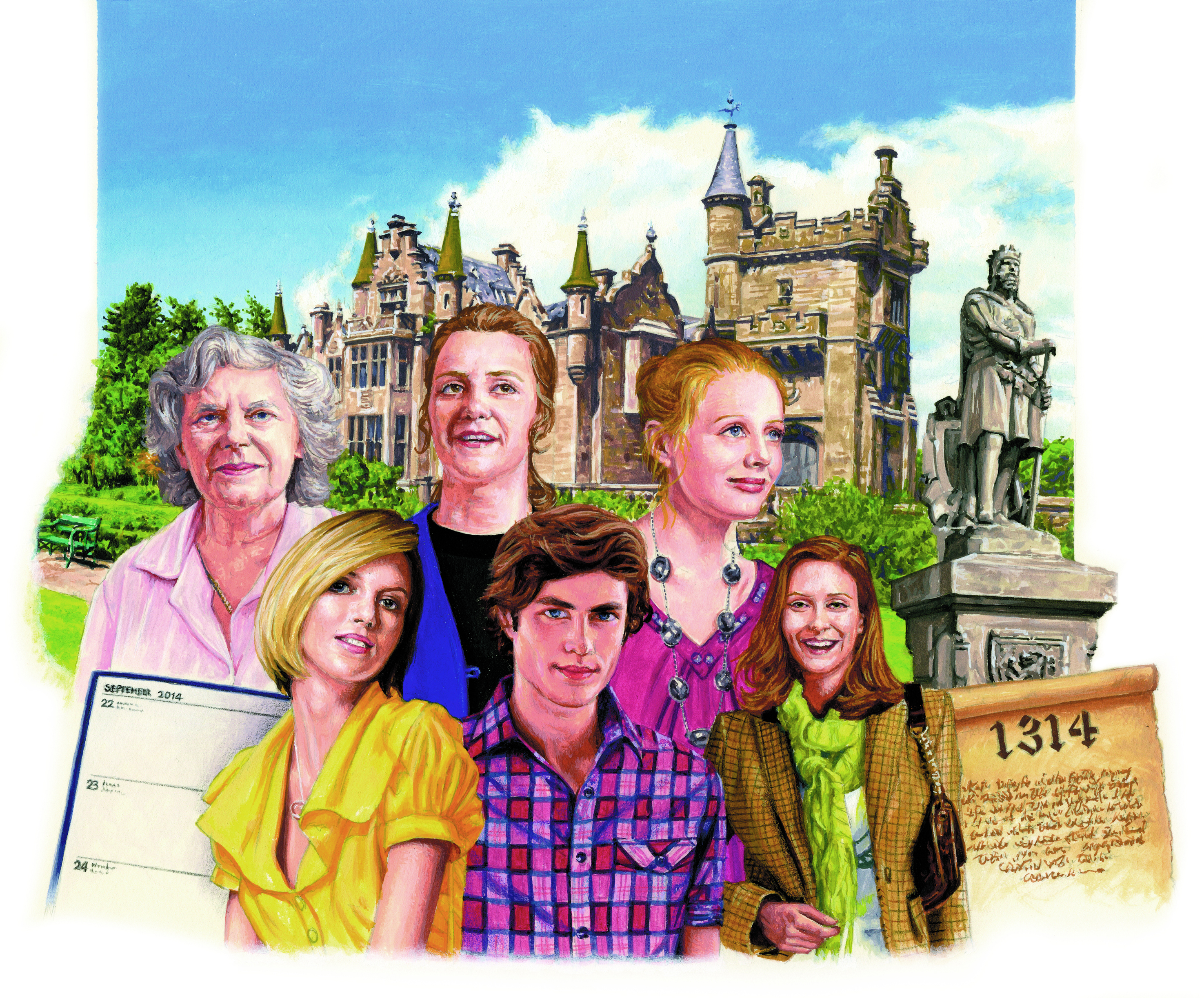

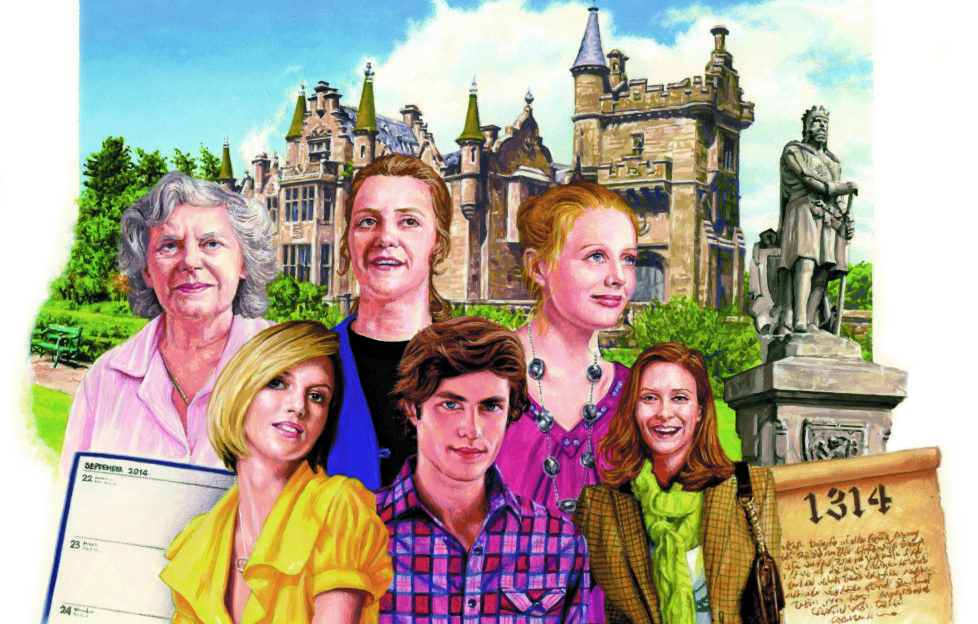

Echoes From The Past – Episode 07

Echoes From The Past by Joyce Begg

« Previous Post- 4. Echoes From The Past – Episode 04

- 5. Echoes From The Past – Episode 05

- 6. Echoes From The Past – Episode 06

- 7. Echoes From The Past – Episode 07

- 8. Echoes From The Past – Episode 08

- 9. Echoes From The Past – Episode 09

- 10. Echoes From The Past – Episode 10

Although not every child could avail themselves of formal education, Stirling town in 1314 did have a school offering the basics in reading and counting, under the leadership of the dominie, Maister Davie Scoular. He was a well-meaning man, happy to instruct Stirling’s boys for a modest return. The main trouble with Maister Scoular was that he was a man of limited education himself. His writing was good enough, and he could count money and weights and measures, which was all most people required, but he had never attended any superior seat of learning.

Most of the time, it didn’t matter. For most people, education was a luxury. Few could read, though they could count where it mattered. On the other hand, someone like Etta at the Black Cockerel would never need to read. She was only a lassie, and a kitchen maid to boot, born for drudgery. But there were others that Maister Scoular could see were meant for greater things.

Hector’s son, Mirin’s brother Murdo, was one of these boys. Murdo was twelve years old, and had been going to the school for four years, during which time he had proved himself an apt pupil. The school days were long, and the conditions harsh, even with an enlightened dominie. And there were always chores waiting for Murdo when he got home to the Black Cockerel in the evenings. There was water to be carried from the well, and dirty straw to be replaced with clean. At the same time, Murdo could see that he was fortunate. He had a kind father and sister, not to mention a proper bed with a heather mattress to go home to. He lacked for nothing, and he knew it.

So it was a strange day when Maister Davie Scoular appeared at the Cockerel and asked for an interview with Hector. On being told of his arrival one Saturday, Hector appeared from the kitchen garden, and escorted the dominie into his own private sitting-room.

“What can I do for you, Maister?” he asked, once he had ascertained that the teacher required no refreshment.

“It’s about your son, Hector.”

“Oh?” Hector was at once suspicious. Murdo had never caused him much concern, but he was a boy after all, and boys meant trouble by definition.

“What has he done?”

“Nothing at all, I assure you. He has been known to truant on a fine day, but which of us has not done that?” The maister crossed his legs and settled back in his chair. “The thing is that Murdo has reached the point when I can teach him very little more. He knows as much as I do, and I suspect if I could find the books for him, he would shortly leave me behind.”

“But Maister Scoular –”

Davie Scoular held up his hand.

“Believe me, sir, I know my limitations, and I suspect that Murdo does, too. So I have this proposition for you, if you are interested. You could take Murdo out of the school, and train him to run a tavern the way you do yourself. Or you could apprentice him to any of the trades in the town. Or you could send him to the monks.”

There was an astonished silence. The monks figured only occasionally in Stirling’s town life. There were plenty of friars – one could see the black-robed Dominicans any day of the week, preaching in the streets, praying for everyone’s souls. There was one in particular, Friar Petrus, who often hovered round the Black Cockerel. But the monks were different. They were not distant as the crow flies, perhaps, since Cambuskenneth was less than a couple of miles away across the river, but they lived very self-contained lives. They were respected, but not much was known about them, apart from their holiness.