Not The Features Ed Blog: Britain’s Long Road To Decimal Currency

Today is the fiftieth anniversary of Britain’s adoption of decimalisation.

From having 240 pennies to the pound, twelve pennies to a shilling and twenty shillings to the pound we moved – not quite overnight – to the system we know now.

Generations of schoolchildren breathed a sigh of relief.

It’s much easier to calculate in tens (fingers help). But a lot harder to deal with the sums involved in counting in twelves. Especially with fractions!

Sarah Jagger’s fun feature in this week’s issue is a nostalgic look back at those days.

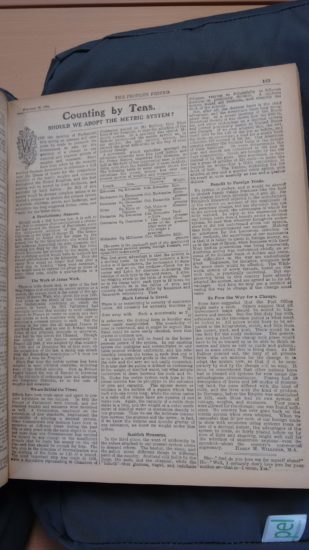

Sarah’s article reminded me of a feature I’d spotted in an old issue of the “Friend” when we were researching for the 150th anniversary souvenir edition.

In the issue dated February 22, 1904, Harry M. Willsher, M.A. wrote “Counting By Tens: Should we adopt the metric system”, about a then-current proposal going through parliament. Clearly, that one did not succeed!

He’s very much in favour of moving to a decimal system. But Harry acknowledges there would be some losses – not least some of the words we used back then.

“Scotland,” he said, “still holds by the lippy, the mett, and the chappin’, while the “bittock” – that glorious, vague, and indefinite distance, varying so delightfully in different districts – is peculiarly Scottish.”

I really want to know what all these were! Do any readers remember them?

Our writer refers to the debate having been going on for some time even in 1904.

Parliament thought about it several times in the 1800s. He hints that there might have been some reluctance to adopt the system partly because it would be to follow in the footsteps of our French and German neighbours. However, he points out that the original proposal had been made by none other than James Watt, of steam engine fame.

My school history lessons had never mentioned this!

A quick trip around the internet yielded much information on the subject. Andrew Carnegie’s 1905 biography of the engineer quotes a letter Watt wrote to fellow scientist Richard Kirwan in November 1783:

“I had a great deal of trouble in reducing the weights and measures to speak the same language; and many of the German experiments become still more difficult from their using different weights and different divisions of them in different parts of that empire. It is therefore a very desirable thing to have these difficulties removed, and to get all philosophers to use pounds divided in the same manner”

He then advocated for adopting the decimal system universally.

Andrew Carnegie observed:

“Science being world-wide, and knowing no divisions, should use uniform terms. Alas! at the distance of nearly a century and a half we seem no nearer the prospect of a system of universal weights and measures than in Watt’s day, but Watt’s idea is not to be lost sight of for all that. He was a seer who often saw what was to come.”

Indeed he was!

Here’s our original article from that 1904 issue, with a transcript to follow.

Photograph by Marion McGivern.

Counting By Tens: Should we adopt the metric system?

With the opening of Parliament this spring an attempt will once more be made to persuade the Government to take up the question of a change in our national and imperial system of weights and measures.

Steps have been taken by the recently revived Decimal Association to introduce a Bill into the House of Lords for the compulsory adoption of the metric weights and measures throughout the United Kingdom and the first reading will be moved by Lord Belhaven and seconded by Lord Kelvin.

No Bill of this nature would be deemed complete unless it included a proposal to abolish the present system of pounds, shillings, pence and farthings and substitute the long suggested florins, cents and “mils” for the latter three.

A Revolutionary Measure

Should such a Bill become law, it is safe to say that no measure of so revolutionary a character has passed the Houses of Parliament since the compulsory adoption of the Gregorian Calendar in the reign of George II.

The housewife would no longer buy her sugar by the pound, but by the kilogramme; she would find the milkman discarding the pint measure, and quoting his fluid by the litre.

The fair maid would purchase her ribbons by the metre, and the scorching cyclist would have to readjust his record performances to the kilometre.

Even the canny Scot would no longer find that after a short stay in London “bang went sixpence,” but would have to express his groan in terms of some other coin.

The Work of James Watt

There is little doubt that, in spite of the fact that France first adopted the metric system as a nation, the system itself is the result of the agitation of James Watt, who, about the year 1793, laid down as the result of his investigations the fundamental conditions on which the system is based.

In 1791 Talleyrand had specifically invited this country to send commissioners to France to confer on metric and decimal reform in both countries with the view of adopting a common system in each.

But the feeling at the time was all against France or anything French. No one in Britain would listen to any proposal, scientific or otherwise, that had its rise across the Channel.

Though the system did not become compulsory in France till 1840, the country adopted it in 1799. On December 9th of that year, on the completion of the law, a medal was struck with the flourishing inscription: – “A tous les Temps. A tous les Peuples.” [For all times; to all peoples.]

Since that time the metric system has been adopted in most civilised countries, including some of the British colonies. Just as Britain lagged behind the rest of Europe in throwing off the old style of reckoning time and adopting the Gregorian Calendar, so in the case of weights and measures.

We are Behind the Times

Many have made efforts to procure legislation on the subject.

In 1841 the Houses of Parliament were burned, and our standard weights and measures were destroyed as well. A Commission, employed on the restoration of new standards, emphasised the desirability of adopting a decimal system.

Other Commissions and motions have been in existence at different times during the past fifty or sixty years with the same object in view. And more than one Commissioner has entered his dissent to any change on the insufficient grounds that he made his money on the old plan and that should be enough for him.

The only step in the direction of decimalisation was the minting of the florin as 1-10 of a pound. We made the most important step in 1895, when a deputation representing 46 Chambers of Commerce waited on Mr Balfour, then First Lord of the Treasury, to urge the adoption of the metric system.

In a specially fine speech Mr Balfour pronounced the metric system as, in his opinion, the only rational system, but showed the great difficulties in the way of compulsory change.

A movement, which embodies amongst its advocates scientific men like Lord Kelvin and Sir Henry Roscoe, engineers like Siemens, as well as the bulk of our commercial men, is something more than the babblings of mere faddists.

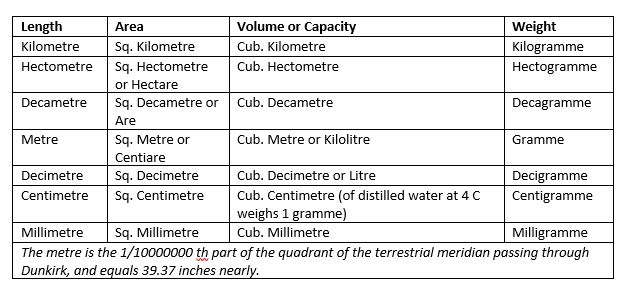

The following table to some extent shows the advantage the metric system has over our present system of weights and measures:-

The first great advantage is that the system is a decimal basis. In the linear columns a kilometre is 10 hectometres, the hectometre 10 decametres, and so on. The prefixes – Greek for increase and Latin for decrease – indicating the relation of each type to the unit measure.

A similar relation exists in the table of weights. Just next inferior, so in the tables of area and capacity the prototypes differ by hundreds and thousands respectively. Thus

Much Labour is Saved

There is no committing to memory of cumbrous tables. All necessity for unwieldy fractions is done away with. Such a monstrosity as ![]() [two and three seven-eighths over twelve, and congratulations to the to 1904 typesetter who managed that!] is unknown; the decimal form is handier and more easily manipulated.

[two and three seven-eighths over twelve, and congratulations to the to 1904 typesetter who managed that!] is unknown; the decimal form is handier and more easily manipulated.

It minimises the possibility of error. And it might be argued that fraud could be more easily checked were this system in common use.

A second benefit is the homogeneous nature of the system. In our existing system the multiples and submultiples in any table proceed without uniformity. The relationship between the tables is such that one is in no case a complete guide to the other.

Thus we cannot easily connect the mile and the acre.

It is true that we define the gallon as containing 10 lbs weight of distilled water. But what simple connection is there between the inch and the lb?

Under the metric system each type in the linear column has its prototype in the columns of area and capacity. The square metre or centiare is the surface of a square which has each side one metre long; while the cubic metre is a cube all of whose faces are squares of one metre side.

Again, the capacity of a cubic decimetre is a litre, and the weight of a cubic centimetre of distilled water at maximum density is one gramme.

Thus we see the intimate connection between the gramme and the metre; in face, if we know the volume and specific gravity of any substance we know its weight under this system.

Scottish Measures

In the third place, the want of uniformity in the values attached to our present system seems to demand reform.

The bushel, the stone, and the gallon mean different things in different parts of the country. Scotland still holds by the lippy, the mett, and the chappin’, while the “bittock” – that glorious, vague, and indefinite distance, varying so delightfully in different districts – is peculiarly Scottish.

A uniform system would aid business, and simplify the work of schools.

But, after all, the decimal basis is the chief advantage, and the Americans have long recognised this.

A recent meeting of the Royal Statistical Society showed how the 2000 lb. ton and other reckonings on a decimal system had proved practically useful in United States and Canada.

If we ever adopted this, the cwt. could still be the 1-20 of the ton as before, and the mett – so convenient a load for a man’s back – become 150 instead of 168 lbs.

Our American cousins employ the decimal basis in the details of their business. Some departments calculate the year and the month at 360 and 30 days respectively.

Merchants buy goods by the 100 instead of the gross. One merchant, in buying a gross of articles at 2¼d each has a little calculation in front of him. The Yankee, reckoning his 100 articles at two and a quarter cents apiece, gets his result at once mentally as two and a quarter dollars.

Benefit to Foreign Trade

No system is perfect. And it would be absurd to abolish handy vulgar fractions like the half and quarter for such symbols as .5 and .25.

Sir Frederick Bramwell objected to the introduction of the scheme on account of the magnitude of the necessary change. But his objection was not to the system itself, the advantages of which he fully realised.

In reply to the statement that our foreign trade would benefit under a decimal system, he said that whatever foreigners understood or did not understand about our system, they fully comprehended our coinage.

Making an allowance for the humorous criticism on the methods, the experience of our merchants is that it is better to quote in foreign money, or, as in the case of Spain, when business with their West Indian possessions was being transacted, American money was understood chiefly on account of its decimal basis of dollars and cents.

The difficulties in the way are undoubtedly great.

Engineers, for instance, recognise how the screw trade would be affected. The Whitworth system of screw threads, based on the inch unit, is practically universal. But engineering firms in this country have already adopted the system. They agree on its advantages.

And here we may see a method of easing the way to change if the change must come.

To Pave the Way for a Change

Some have suggested that the Post Office might make a start. Others that the Government scales maps to kilometres and metres.

But the first duty lies with education.

We would have to adjust all prices to the kilogramme, metre, and litre from the pound, yard and pint. There would be a fine field for the ready reckoner.

The generation during which the change took place would have to be so trained as to be able to think in metres and litres as well as yards and gallons. And to some extent, this is underway.

As Mr Balfour pointed out, the duty of all private firms who are anxious for the change is to adopt the system now. This way, if it is to be compulsory by and by the change will be easy.

Other nations have had to discard old systems for new under disadvantageous circumstances. France had 50 descriptions of livres and 100 modes of measuring land. The aune differed with the kind of cloth, and the livre with the kind of produce.

In Germany, before the Empire was established in 1871, each State had its own system of coinage, weights and measures. The Government allowed four years for the change, but one was sufficient.

No country has ever gone back on the metric system when once adopted.

When we remember that 60 per cent of our foreign trade is done with countries using systems more or less of a decimal nature, the advantages of the system in trade, so fairly placed before us by men of light and standing, might well call for the attention of statesmen anxious – even despondent – about the country’s commercial supremacy.

HARRY M. WILLSHER, M.A.

About the writer

Who was Harry M. Willsher?

An entry on the website of the Wighton Heritage Centre, a specialist collection of Scottish music, part of Dundee’s Local History centre, provides a short biography.

Harry M. Willsher, M.A., D. Litt. (1873–1958), sometime Librarian of University College, Dundee (now the University of Dundee), who was an authority on old Scottish music, and instrumental in restoring numbers of airs. He was an Honorary Lecturer in Scottish Music at St. Andrews University, and both wrote and produced broadcasts on the subject of old Scottish music.

He sounds like a man of many talents and interests!

For more fascinating Features from “The People’s Friend”, click here.